A Squirrel, a Schnauzer, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

I came home from a long day of teaching in mid-January of this past year, tired in that uniquely teacherly way where your voice feels a half-step lower and your head is still buzzing with lesson plans and half-finished conversations. When I walked into the bedroom, I noticed Io outside the window, standing perfectly still, his stubby little fluffy nub of a tail quivering. And in his mouth, dangling from his white beard, was a limp squirrel.

He didn’t whine. He didn’t bark. He simply stood there, displaying his prize through the glass, waiting with unwavering confidence for us to notice him, as though he were presenting the culmination of a very important personal project. And there he was—our gentle, snuggly, universally adored Mini Schnauzer, beloved not only by my wife and me but by every human who has ever crossed his path—holding the very clear evidence of a life he had just taken.

My brain leapt immediately, involuntarily, to one conclusion: “Our dog is a little murderer.”

Of course, Io wasn’t committing a crime. He wasn’t breaking some moral code. He wasn’t even doing anything unusual for his species. Io acted out of instinct—older than squeaky toys, older than his groans when you try to move him off your pillow and he goes limp like a ragdoll, older even than the many generations of domestication that have softened dogs into the companions we’ve turned them into.

But this is what humans do: We narrativize.

Nature does what nature does, and we immediately assign intention, symbolism, even ethical weight to it. A dog catches a squirrel and we tell ourselves a story about violence, about innocence lost, about moral disruption.

Io didn’t moralize. I did. And that gap between his world and mine is where something interesting cracked open.

That proud, frozen stance outside the window—tail nub vibrating, eyes shining with expectation—reminded me that every creature, no matter how domesticated or adored, carries hidden layers of instinct, wildness, ancient behavioral scripts, and a lineage of reactions older than awareness. We tell ourselves—and each other—stories like “I would never do that,” or “That’s not who I am,” or “I’m the calm one / gentle one / predictable one.” But beneath our neat self-definitions lies something messier, something older, something more honest.

Just like Io, we all contain capacities we don’t expect to use. We all carry instincts we rarely confront. We all hold wildness beneath the surface.

Io wasn’t being “out of character.” He was revealing the parts of himself that aren’t shaped by our praise or expectations.

And I realized I do the opposite. I often hide the parts of myself that don’t fit the narrative I want to tell.

When we finally took the squirrel away—Io clearly crestfallen, still trying to make sense of why we would reject such an obviously magnificent accomplishment—he trotted off with a strange mix of dignity and disappointment. But in that tiny interaction, I understood something: Io believed he had done something good. Something meaningful. Something praiseworthy.

The moment, as he understood it, was simple: He hunted, he succeeded, and he presented his success to his people. And I, as a human, inhabited that same moment with a fundamentally different internal logic: I gave it meaning, judged it morally, built a narrative around it, and then worried about the implications.

Io’s unexpected trophy taught me something about the nature of being alive: Instincts—whether his or mine—aren’t flaws. They’re part of our design, part of our inheritance. And when I assume that people (including myself) are simple, predictable, “tame,” or fixed in identity, I’m forgetting everything evolution has layered within us.

The day Io killed his first squirrel didn’t make him a murderer. It made him honest. It reminded me that we are all, in small and sometimes startling ways, continuations of something ancient—something not fully under our control, something we can acknowledge without shame.

Io actually didn’t change at all that day.

But I might have.

What I’ve Learned About Writing from Teaching Fifth Graders

When you teach writing to ten-year-olds, you start to see writing less as an artform and more as experimentation. Each and every sentence is its own small hypothesis: If I say it this way, people will better understand me. In this sense, every young writer is an engineer of meaning, testing—whether purposefully or not—how much the bridge of language can hold before it collapses.

Adults tend to forget this. We try to polish the experiment before we even run it. We try to control all the variables. But children remind you that the magic of writing lies in the unpredictable space where confusion turns into clarity. It lies somewhere in the collision of the understanding of the required mechanics and the freedom and audacity of expression. Here are some lessons I’ve learned about writing from my time teaching fifth grade students.

Clarity Is an Act of Empathy

You can’t hide behind cleverness when you’re explaining what a metaphor is to a room full of kids who are still learning that “the sun smiled down on me” doesn’t mean the star at the center of the Solar System has a face. Teaching forces me to slow down and to make each sentence carry its own weight. Practically everything read in the classroom gets the meticulous attention of a close read—and so everything written should get that same treatment. When I write now—short fiction, lengthy fiction, scripts for video essays, or even emails—I can almost hear my students asking, “Wait, what does that mean?” And if I can’t answer their question simply, then I probably don’t fully understand it myself, and I should almost certainly rephrase it—or omit it altogether.

Clarity, I’ve realized, isn’t merely simplification, but empathy. It’s choosing to guide a reader rather than impress them. It’s not holding their hand or spoon-feeding them, but rather organizing ideas with logic and consistency so that one idea flows into the next in a way that is easy to follow no matter how difficult the subject matter. It is in this sense I suppose you could consider this to be the “Golden Rule of Writing”: Write in a way that you would want to read.

Curiosity Beats Perfection Every Time

When we start a writing project, my students are fearless—this is a quality of theirs of which I am exceedingly envious. They don’t worry about whether their idea is “good enough.” They just start writing. Their stories end up being about things like a laundry monster made of dirty socks, or a dragon that’s allergic to fire, or a hamster who accidentally becomes the ruler of the moon, or a time-traveling goldfish who can only go forward five seconds at a time. Somewhere along the way, we adults lose this reckless, creative curiosity and start editing before the sentence even exists.

Watching my students create reminds me that discovery usually happens during writing, not before it. Sometimes the story changes shape halfway through—a side character takes over, the conflict fizzles out, or the ending sneaks up from a completely different direction—and that’s fine. In fact, not only is it fine, but often it’s optimal! And it’s certainly better than sitting paralyzed in front of a blank page just waiting for genius to strike.

Constraints Are Creative Fuel

Fifth graders thrive on structure. If you tell them to “write anything you want,” they will usually just freeze up completely, paralyzed by the enormity of endless possibility. But if you give them a quirky prompt—something specific yet playful, like “Write a story that begins with the words ‘It all started with a sandwich’”—then suddenly the room becomes positively abuzz with creative energy. Pencils start scratching, muffled laughter ripples across the room, and even the quietest and least confident students begin to find their footing. The clarity of direction doesn’t limit creativity—it liberates it by giving them a starting point, or a boundary to push up against.

As a writer, I’m very much the same way.Give me utter freedom and I’m likely to stare at the blank page for hours. But give me a constraint—a deadline; a word limit; a strange, self-imposed challenge (“Write a short story from the perspective of a sentient nebula”)—and suddenly the synapses start firing. The paradox of creativity is that it flourishes best when it has something to resist. There is no limit to a properly and thoroughly exercised imagination, but it definitely needs walls to ricochet ideas off of.

Voice Is Born from Play

When my students first start writing, they mimic their favorite authors. Their stories sound suspiciously like Percy Jackson or Harry Potter fanfiction. But the more we laugh and experiment—rewriting fairy tales as news articles, or turning science lessons into haikus—the more their authentic voices start to surface.

Adults are no different. We spend so much time trying to sound like “serious writers” that sometimes we forget the joy of sounding like ourselves. The voice worth finding isn’t the most polished one—it’s the one that can still surprise you.

Writing Is Always About Connection

Every time a student brings me their story, they’re not just asking for feedback—they’re asking, Did you see me? Did you understand what I meant?

And isn’t that what we’re all doing when we write? Whether it’s a novel, a poem, or a blog post, we’re trying to bridge the gap between our private thought and someone else’s experience. We’re saying, Here’s how I see the world. Does it look that way to you, too? Teaching fifth graders has taught me that writing doesn’t have to be a solitary act. Teaching young writers is helping to strip away the pretense. It’s made me more patient, more playful, and a little more forgiving of the messy drafts—both theirs and mine. If there’s one universal truth about writing, it’s this: you learn by doing; you get better by failing; and you find joy not when the work is perfect, but when it’s unique.

Making the Implicit Explicit in Literature

I was reading How to Read and Why by Harold Bloom, and in this book he states that literary critics practice their art in order to make what is implicit in a book explicit. That phrase struck me. It’s quite simple, but it neatly captures the whole enterprise of criticism, interpretation, and—if I may extend Bloom’s claim—a great deal of teaching as well.

I’ve been reading The Secret Garden with my fifth graders. We’re doing a close reading of the book, and so, in addition to the dubious (but they don’t know any better) Yorkshire accent I affect to enliven the story, I stop every so often to point out a notable character detail, or to recognize an important plot development, or to underline the thematic relevance of a scene, or to ask if they know what a word means, or simply to revel in some lovely prose (of which this book is positively littered, for those who have not read it).

The other day, we had just finished Chapter 11. In this chapter Mary Lennox, the sickly and prickly little girl who began the book by liking no one and being liked by no one, experiences a small but significant transformation. She admits she now likes not one, not two, but five people. She never imagined she’d like even a single person, let alone five. And so she names them: there’s Martha; and Martha’s mother; and Martha’s brother, Dickon; and old Ben Weatherstaff, the manor’s groundskeeper; and the lovely little bird—a robin—that helped Mary find her way into what she now calls her “secret garden.”

One of these things is not like the others. My students caught on immediately when I pointed it out: the robin is not a person. And yet Mary counts it among her growing circle of affection. Why? Because, of course, the robin is not merely a bird. In the symbolic world of the novel, the robin represents nature itself, beckoning Mary toward friendship, renewal, and healing. The bird is a living signpost pointing the way into the deeper themes of the story.

So I said to my students, in what I thought was a simple clarification: “Obviously, the bird isn’t just a bird.”

I meant, of course, that the robin functions symbolically—that often in literature, animals, objects, and images can carry meanings beyond themselves. But one of my students raised their hand with an earnest question:

“Is the bird a shapeshifter?”

Now, this is hilarious. But it is also revealing. In that moment my student was doing what Bloom describes: trying to make the implicit explicit. They recognized that the robin meant more than itself, and in their imaginative leap, they went straight to the most literal possible explanation. If the bird is more than a bird, maybe it is secretly a person in disguise.

This may sound fanciful, but it gave me pause. Because when we teach literature—or when we read closely ourselves—we are not merely uncovering hidden “answers.” We are training ourselves to perceive the layered nature of meaning. A child’s guess that the robin is a shapeshifter is not “wrong.” It is an early, playful attempt to grapple with symbolism, metaphor, and the way stories invite us to read on multiple levels at once.

Why Making the Implicit Explicit Matters

Literature is always operating in two registers: the surface narrative and the undercurrents of implication. To read well is to navigate both. On the surface, Mary likes five “people.” But implicitly, she is acknowledging her first steps toward connection, toward an openness that extends even to the natural world. Without pausing to notice that she counts the robin among the humans, we might miss the subtle work Frances Hodgson Burnett is doing—showing that nature itself has become part of Mary’s growing circle of relationships.

This is why we slow down and linger over details. This is why Bloom insists on making the implicit explicit. Without it, we skim along the top of stories, and we never descend into the deeper waters where meaning, mystery, and transformation live.

Teaching the Habit of Attention

In a classroom, this practice becomes even more important. Children are natural readers of the implicit—they grasp quickly at patterns, they delight in hidden meanings, they leap (sometimes wildly) to make connections. But they also need guidance. They need to be taught not only that texts contain more than meets the eye, but that drawing those meanings out is itself a joyful and serious part of reading.

So I stop. I point. I highlight and underline. I ask questions. Why does Mary like the robin? Why does she describe him as a person? What might Burnett be saying about nature, about friendship, about healing? In these small acts, I am not “telling them what to think.” I am training their eyes to see what is already there, waiting just beneath the surface.

And if they occasionally leap to shapeshifters, so much the better. Those leaps can help us to remember that imagination is the engine of interpretation. Even the most careful literary critic is still, at heart, a child asking: “What if the bird is more than just a bird?”

The Larger Work of Reading

When Bloom talks about making the implicit explicit, he is not only talking about symbolism or metaphor. He is pointing us toward the very reason we return to books again and again. Reading well demands that we become translators of implication. We take what is quietly humming in the background of a text and bring it forward into the light of thought and discussion.

This is also why books endure. The Secret Garden is not simply a charming story about a little girl who discovers a locked patch of earth. It is a book about resurrection, about the healing of body and spirit, about the ways in which life reasserts itself against decay and despair. None of that is written baldly across the page. It is there in implication—in the robin, in the ivy-covered door, in the garden itself.

The Bird Is and Is Not a Bird

So yes, the robin is a bird. But no, the robin is not just a bird. Reading well requires us to hold those two truths at once. Literature always asks us to see both the literal and the figurative, the explicit and the implicit.

My student’s question—“Is the bird a shapeshifter?”—is funny because it literalizes the metaphor. But it also demonstrates that the work of making the implicit explicit begins in wonder. It begins in the willingness to ask questions, to stretch our imaginations, to assume there is more to the story than what is first apparent.

And that is what makes reading not solely an academic exercise, but a profoundly human one. We are creatures who positively crave meaning. We look at a bird in a garden and we suspect it might be more than just a bird.

And the magic of literature is that it rewards that suspicion.

Why I Track My Reading (and What It’s Actually For)

I track every book I read.

Religiously. Compulsively. Joyfully.

I use Goodreads to log titles and dates. I keep an Excel spreadsheet that catalogs my entire personal library, sortable by author, genre, and whether I’ve actually read it or am merely hoping to someday. I record YouTube videos reflecting on what I’ve read, what I’m reading, and what’s slowly clawing its way up my towering, guilt-laced TBR. I jot down notes or excerpts in a physical commonplace journal (though, admittedly, that’s more sporadic than it is sacred).

So when I recently watched a Memoria Press video in which several members of a group of adults (well-read, thoughtful adults!) casually mentioned that they don’t track their reading at all, I felt a strange, complex combination of awe and disgust.

They just … read?

No spreadsheet? No charts? No annual wrap-up posts complete with genre breakdowns and five-star favorites? No log to look back on with quiet pride (or self-reproach)?

I won’t pretend I’m not intrigued by that approach. There’s something beautifully unburdened about it. But I’m also not giving up my system anytime soon. Because for me, tracking my reading isn’t about showing off, or chasing numbers, or wringing productivity out of a pastime that’s already deeply nourishing on its own.

It’s about attention. And retention. And gratitude.

A Conversation with Myself

At its most basic level, tracking what I read is a way of staying in conversation with my past self. That version of me who picked up No One Is Talking About This on a whim during a rough patch in November of 2024? Or the me who finally got around to reading The Dispossessed after a decade of false starts? The me who couldn’t get through the assigned reading of Moby Dick as a teenager? They’re still in there, still shaping the contours of my inner world, and my reading log is one of the few places where I can go back and listen to them.It’s not always deep. Sometimes I’m just noting a title and a finish date. Other times, I’ll write a few sentences about why something hit me the way it did (or didn’t). But even that little gesture of recording it gives the experience a kind of permanence. It says: This mattered.

Measuring What Can’t Be Measured

Of course, there’s a danger in turning reading into a performance. If you’re not careful, tracking can become tallying, and tallying can become competing—even if it’s just with yourself. You start chasing totals. You feel guilty about long books, or books you abandon halfway through. You start comparing your reading pace to strangers on the internet who seem to inhale five books between breakfast and lunch and then ten more before dinner.

But here’s the trick: the numbers are not the point. They’re just scaffolding.

What I really want to measure isn’t how many books I read, but how deeply they reached me. How much they asked of me. How much they changed me.

A spreadsheet can’t quite quantify that. But it can create the conditions for reflection. It can slow me down enough to ask: Why this book? Why now? What did it stir within me?

The Habits of Attention

I’ve stated this a million times, but I teach fifth grade science and literature, which means I spend my days trying to help ten-year-olds pay attention to the right things. Not just to facts and dates, but to ideas. To structure. To character. To detail. To beauty.

And one of the most important things I’ve learned is that attention is a muscle. It has to be trained. Reading helps with that.

But so does tracking.

When I keep a record of what I’m reading, I find that I read more deliberately. I notice patterns. I realize I’ve read five books in a row by men and none by women. I realize I’ve been stuck in the same genre rut for three months. I realize I keep saying I want to read more poetry, and then not doing it. My tracker keeps me honest. It makes me a better reader—not because it tells me what to do, but because it helps me see what I’m actually doing.

And from there, I can adjust. With intention.

Sharing the Journey

There’s another reason I track my reading: I want to share it. Not to signal virtue or aesthetic superiority, but to connect.

Books are the most generous kind of conversation. But that conversation deepens when you bring someone else into it—whether that’s a student who’s reading Harry Potter for the first time, a friend who just finished the same book you did, or a stranger who stumbles across your YouTube channel and decides, on your recommendation, to give Cryptonomicon a try.

By logging my books, I create a kind of trail of breadcrumbs. A path others can follow, question, deviate from, or deepen. It’s a small act of curation. A signal: Here’s what I’ve loved. Maybe you will, too.

When I Don’t Track

With all this being said, not every reading experience makes it into the spreadsheet. Sometimes I pick up a book, read twenty pages, and set it down with no intention of returning. Sometimes I’m reading aloud to my students or thumbing through a reference work I’ve owned for years. Those moments don’t always get cataloged, and I think that’s OK.

The point of tracking, for me, isn’t to build a flawless archive. It’s to stay attentive. To keep reading as an active, reflective, relational practice. To remember that books aren’t just something I consume, but something I commune with.

And if that communion sometimes requires an Excel sheet with color-coded tabs? So be it.

Final Thoughts

Whether you track your reading obsessively or prefer to let books wash over you unrecorded, the important thing is this: read with presence. Read with curiosity. Read with the knowledge that every book—even the odd ones, the disappointing ones, the ones you forget almost immediately—is part of the longer story you’re writing with your life.

And if you happen to write it down along the way, all the better.

What Book Covers Teach Us About Visual Literacy

I tell my students that every book talks to you before you open it.

Sometimes it whispers. Sometimes it shouts. Sometimes it beckons mysteriously from across the bookstore with a glint of foil or an odd texture. But one way or another, it speaks—and you decide, in a fraction of a second, whether you’re going to answer.

That’s the power of a book cover.

We don’t always acknowledge it. We’re trained to say things like “don’t judge a book by its cover,” as though the cover were some sort of lie, or a distraction. But that old phrase is wrong on two fronts: first, we do inevitably judge books by their covers, and constantly; and second, book covers aren’t lies. They’re arguments. Visual, compressed, sometimes poetic arguments about genre, tone, identity, and intent. And learning to understand those arguments is part of what we call visual literacy.

As a designer, I’ve spent hours tweaking the space between a serif and a swirl, adjusting kerning until a word feels right. As a teacher, I’ve watched students gravitate toward books on our classroom shelves not because of the summary on the back cover, but because of the way the front cover spoke to them. And as a reader, I know the quiet thrill of recognizing a pattern across covers—a particular style of illustration or layout—and knowing, instinctively, that this book belongs in the same conversation as others I’ve loved.

Visual literacy is, simply put, the ability to read images. To analyze, interpret, and make meaning from what we see—not just in art, but in design, photography, film, advertising, social media, you name it. And like verbal literacy, it’s not innate. It’s learned. It’s practiced. It’s taught.

Covers Are Codes

When you look at the cover of a book—whether it’s minimalist and typographic or lush and illustrated—you’re not just looking at decoration. You’re looking at a set of semiotic signals. A language of form.

Consider the modern sci-fi novel. Angular sans-serif fonts. Lots of black. Metallic accents. Some abstract pattern that hints at technology or stars or time dilation. That’s not accidental. That’s a code—a shorthand telling you, “This is speculative. This is sleek. This might bend your brain a little.”

Compare that to a quiet literary novel with a soft-focus landscape or some sort of abstract backdrop. Or a thriller with jagged text and stark contrast. Or a romance with looping script and soft pinks. These are all visual choices made not just to reflect the content but to shape the expectation of the reader.

Design is always in conversation with genre. But the best covers don’t just mimic the market—they subvert it. They play with our expectations while still working within a shared visual vocabulary.

Teaching the Image

I teach fifth grade, and even at that level—especially at that level—students respond to visual cues with a kind of raw immediacy. They might not have the vocabulary to explain why one book looks “serious” and another looks “fun,” but you know what? They know. And part of my job is helping them articulate that knowing.

When we talk about book covers in class, we ask questions like:

• What colors are used, and what mood do they create?

• What might the typography tell you about the tone of the story?

• What’s pictured? What’s not? Why do you think that choice was made?

• If you had to guess the genre from the cover alone, what would you say?

Sometimes we even redesign covers—taking a book we’ve read and asking students to create their own visual interpretation of it. Not just to draw a scene, but to capture the feeling. To consider how their image might speak to someone else. It’s an exercise in empathy, in aesthetics, and in attention.

Visual literacy is not really about being “artsy,” per se. It’s about being attuned to how design shapes understanding. And in a media-saturated world, that’s not optional. It’s essential.

The Ethics of Attraction

Of course, covers aren’t neutral. They reflect trends, but they also reinforce them. When every YA fantasy novel features a similar pale girl in a crown, we have to ask: what kinds of stories are being signaled as “worthy”? Who gets to be on the cover? Who gets erased? The visual landscape of publishing tells a story about power—about what sells, and who decides what sells.

Part of becoming visually literate is learning to see those patterns, as well as to question them.

We teach students to recognize bias in texts. We should also teach them to recognize bias in images. What gets represented and how? What stereotypes are repeated across genres? What assumptions are embedded in style?

This is one of the places where design meets critical thinking.

What Covers Can’t Do (and Why That Matters)

And yet, for all their power, covers are also fragile things. Misleading. Market-driven. Occasionally betrayed by their contents. Some of my favorite books have had baffling covers—either too vague, too loud, or just wildly off the mark.

Which is part of what makes reading so delightful: the dissonance. The act of stepping past the surface and discovering something messier, deeper, stranger.

It’s a reminder that even the best cover is only a doorway. It opens. It invites.

But the real story begins inside.

Final Thoughts

Book covers are both marketing tools as well as visual texts. And like any text, they can be read, misread, deconstructed, admired, and critiqued. The more fluent we become in visual language, the more deeply we engage with the world around us—not just as passive consumers, but as curious, creative participants.

So the next time you pick up a book, pause for a moment. Look closely. Ask what it’s saying—before you ever read a word of it.

Finding Time to Read

Every so often, someone asks me how I find time to read.

The tone varies. Sometimes it’s admiring. Sometimes it’s accusatory. Often it’s said with a kind of mild despair, like I must have access to some secret reservoir of hours that the rest of the world wasn’t issued.

But I don’t.

I teach fifth grade science and literature, which means I am perpetually grading, planning, emailing parents, responding to parent emails, and gently reminding students when their homework is due. I also write, make videos, make music, coach soccer, and play guitar in my church’s worship team. My time is certainly no less limited than anyone else’s.

Here’s the thing: I’ve never thought of reading as just a hobby. It’s not a luxury I squeeze in at the edges of real life. Reading is the life. It’s how I think. How I rest. How I stay connected to something larger than the noise of to-do lists and classroom chaos.

Reading is the slowest magic there is. It asks nothing but time. Not talent. Not money. Just time. And in return, it offers everything: new voices, new ways of seeing, new ways of being. Books don’t care if you’re tired or behind or feeling inadequate. They wait.

And when you come back to them—when you choose, again and again, to open a book instead of turning on the TV or launching into a video game—you start to feel time stretch a little. Just a little. Long enough to slip into a sentence and find yourself somewhere else entirely. (This isn’t to say that a great TV show or video game doesn’t have value—they absolutely do, though, I would argue, in moderation.)

I try to teach my students this. That reading isn’t an assignment to get through, but a portal. That a book is a way of slowing down time. That the act of sitting still with words is a kind of resistance in a world built to keep you endlessly and mindlessly scrolling.

They don’t always get it. Honestly, I didn’t always get it at their age, either. But every once in a while, a kid gets their mind blown by a book, looks up with eyes wide, and says, “That was really good!”

And I can’t help but be thrilled by this. Because I know it wasn’t just entertainment. It was transformation—tiny, maybe, and mostly invisible, but undeniably real.

So if you’ve been too busy to read lately, that’s OK. The books will wait. But when you’re ready, carve out ten minutes. Just ten. Not to “be productive,” not to hit a goal. Just to read. To practice the slow magic again.

And let time open up around you.

The Space Between Knowing and Wondering

I teach fifth grade science and literature. Which means, on any given day, I might go from explaining the phases of the moon to asking a room full of ten-year-olds what they think The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is really about. I’m always straddling the line between fact and fiction, data and dreams, the concrete and the speculative. And I’ve come to believe that creativity lives exactly there: in the space between knowing and wondering.

Teaching is often framed as the transmission of knowledge, and sure, there’s definitely some of that. I’ve got vocabulary words to cover and standards to hit and a pacing guide that insists students need to understand a plethora of scientific concepts by April. But the best moments in the classroom happen not when something is known, but when something is almost known. When a student squints at the board and says, “Wait … does that mean what I think it means?”

That’s where the magic is.

It’s not so different from reading, really. My favorite books, the ones that haunt me long after I’ve shelved them, rarely hand me perfect answers. Instead, they reverberate with implication. They circle around truth like a hawk. Books like Roadside Picnic, The Left Hand of Darkness, Maxwell’s Demon, or Infinite Jest make their meaning in the tension between clarity and mystery. They trust me to do some of the work. They trust me to wonder.

When I write, I try to honor that same space. I don’t want to outline every single beat (though a roadmap can certainly be handy). I don’t always know what a piece is “about” until I’m fairly deep into the process. Sometimes, I write a scene or a paragraph or a line just because it feels right—because it contains something unresolved. And then I try to follow that thread wherever it leads, even if it pulls me somewhere uncomfortable.

I think this is what creativity really is—not some lightning bolt of inspiration, but a sustained willingness to sit with the half-formed, the ambiguous, the not-yet-finished thought. To be okay with the in-between. To teach, to read, to write, to make art—all of it requires us to hover in that liminal space and say: “Let’s see what happens if…”

And that’s why I love doing what I do. Whether I’m in the classroom or staring at a blinking cursor, I get to spend my days dwelling in wonder.

So here’s to the space between knowing and wondering. May we never fully leave it.

Keep the Door Open: On Catching Good Ideas Before They Vanish

The first thing to understand is that the ideas are not yours. Not really.

You’re not a well or a spring or even a clever little idea-machine. You’re more like a resonant cavity. A hallway with good acoustics. A frequency that, if tuned just right, might just hum. Might just vibrate with something strange and startling.

You are, in short, a host. A cracked-open door. And the creative process is not so much a journey of invention as it is a long and difficult apprenticeship in receptivity.

It is also, paradoxically, a discipline.

This is the first paradox of creativity: that in order to generate the seemingly effortless, spontaneous, lightning-strike originality we call a “great idea,” you must show up at the same time every day. You must punch the clock. Sweep the floors. Boil the water. You must clean and re-clean the altar so that, if the gods ever do decide to visit, they won’t trip over your laundry.

But how do you keep having ideas? Not just once—when you’re young and ravenous—but over years? Across novels? From project to project? In seasons when the well goes dry and all the air seems to have been vacuumed out of the room?

I won’t pretend I have a magic formula. But I’ve learned a few things. Or maybe I’ve just failed in enough interesting ways that I’ve started to notice the patterns.

1. Think Weird, Read Weird, Live Weird

Great ideas often come from collisions—friction between disciplines, between categories, between voices that were never meant to be in the same room. If you only ever read space opera, your brain will start to pattern itself like a space opera. If you only ever talk to other indie authors on Discord who are writing the same three stories in a different flavor, you will unconsciously become a remix.

And remixes are OK, and they have their place, but to have unique ideas, you need to introduce contamination.

Read Proust and then read a NASA white paper. Read Octavia Butler on interdependence and then read a handbook on urban wastewater management. Watch a YouTube video on medieval siege weapons, then interview your grandmother about her youth. Play Disco Elysium, then go to a soccer match.

Diversify your cognitive portfolio.

What you’re doing here is stockpiling flint. Later, when you’re exhausted or stuck or desperate to come up with the Next Thing, your brain will strike two of these weird rocks together—and if you’re lucky, and you’ve been faithful to the process, and the gods aren’t entirely indifferent that day—you’ll get a spark.

2. Let Boredom In

We are terrifyingly good at avoiding boredom now. There is a device in your pocket, perhaps even in your hand right now, that is capable of flooding your brain with novelty at a frequency no pre-digital human ever experienced. Infinite scroll. Infinite noise.

But the creative mind needs boredom. It needs a space in which nothing is happening so it can begin to hallucinate.

When was the last time you stared at a wall?

Not a Pinterest wall or a vision board or a spreadsheet. I mean a blank wall. A dull one. One that does nothing for you. When was the last time you stood in the grocery line and didn’t check your phone? Sat in traffic without a podcast? Took a walk without tracking your steps?

If you want more ideas, you must allow more nothing. You must resist the anesthetic of the endlessly curated feed.

Let silence creep in. Let the inner monologue get weird. Trust that, given enough space, your brain will start filling in the gaps. That it wants to play, to imagine, to make. You just haven’t been letting it.

3. Obsess Over Questions, Not Answers

I think this is the main thing. The people who keep generating extraordinary, original work are not people who have found something; they are people who are haunted by something.

They are infected with a question.

What is identity if memory can be altered? What does it mean to be human in a post-biological era? What happens to love in the face of entropy?

These are not answerable questions. That’s the point. A good question gnaws at you. You chase it down across projects, across mediums. You revisit it in a short story, then in a novel, then in a video essay, then in the form of a sculpture you’re ashamed to talk about.

The more obsessed you are with the question, the more variations your mind will find. New angles. Fresh metaphors. The creativity doesn’t come from the pursuit of originality—it comes from the pursuit of understanding.

Which is really just to say: find the questions that break you open. And keep asking them in stranger and stranger ways.

4. Stay Moving

This is maybe the most practical advice I have.

Get up. Go for a walk. Take a shower. Clean something. Do the dishes. Get on your bike and go for a ride.

Something about locomotion—rhythmic, repetitive motion—gets the gears unstuck. It short-circuits the overthinking. It engages some parallel processing loop. Some of my best ideas (and I suspect yours too) arrive somewhere between miles one and two of a Zone 2 jog.

You don’t have to be an athlete. You just have to be in motion.

5. Give Yourself More Constraints

This one feels counterintuitive, but it’s important.

When you’re stuck, don’t try to “open up” the idea. Try narrowing it. Give yourself fewer tools. Fewer options. Smaller boxes.

Write a story in 500 words. Write a song with only three chords. Build a narrative that only uses second-person present tense and occurs within a single elevator ride. Draw the scene using only circles.

Creativity thrives in limitation. It needs friction. Resistance. Something to push against. Infinite possibility is not fertile ground—it is a blank canvas so blinding it paralyzes the hand.

6. Make It Ugly First

This is the one I struggle with most. You probably do too.

But perfection is a creativity killer. If you want more ideas, more breakthroughs, more genuine newness in your work, you must be willing to create garbage.

The first draft is a swamp. It should be a swamp. You’re wading through it with a headlamp and a notebook, trying to figure out what lives here. You’re not building the cathedral yet—you’re spelunking. Surveying. Taking notes in the dark.

So allow the mess. Invite the ugly. The act of making something—anything—is what keeps the idea channels open. You don’t wait until you have a great idea to start working. You start working, and the great idea stumbles in around hour four, confused but intrigued.

Here’s the thing they don’t tell you in school: the great idea isn’t the goal. It’s a side effect.

The real goal is to remain in process—to live, daily, in that trembling space between mystery and articulation. To become a faithful observer of the strange, the beautiful, and the broken. To listen. To follow. To show up.

The rest will come—but only if your door is open.

And the altar is swept.

Brilliant Nonfiction Books You Should Read

I hold a certain sort of reverence for nonfiction books that can manage to be engaging in the same way fiction can be … books that can strike that balance between offering clarity and inspiring awe—in a word, they’re readable, and enjoyably so. Today, I want to talk about five of my favorite nonfiction reads.

Now, I have a background in science and astronomy, so I tend to gravitate toward nonfiction books with a scientific bent, so it’s probably not surprising that all five of these picks are directly science-related. When I was picking them out, I wanted to choose books that reshape perceptions, books that offer both general knowledge but also make you think. Each of these books, in their own way, has left a permanent mark on me. There’s everything from deeply human dramas of scientific discovery to the musings of mischievous geniuses. These are true stories that explain aspects of the world as well as make me grateful to be living in it.

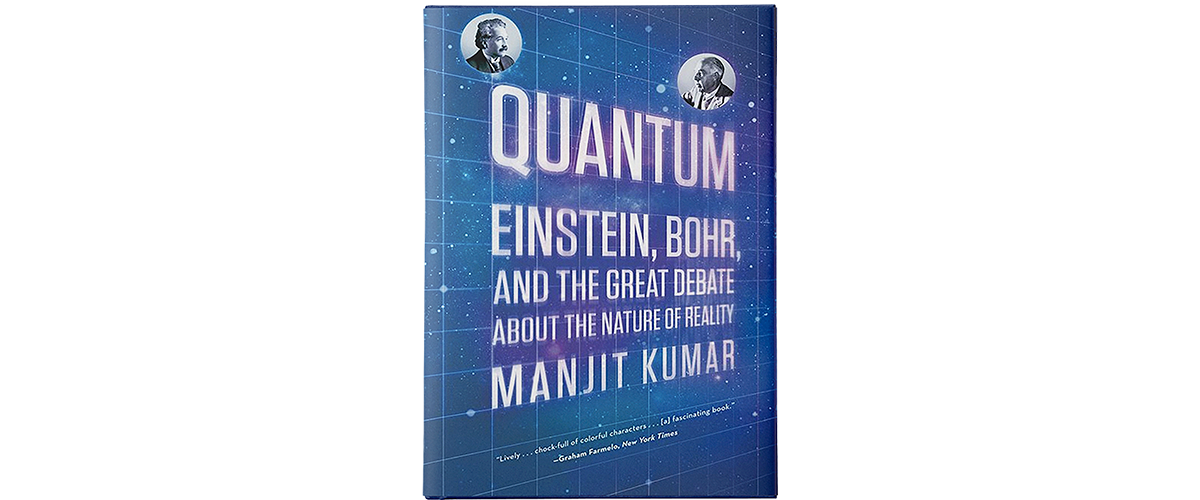

5. Quantum by Manjit Kumar

The thing that so often makes popular science books fall flat is that they need to do two things at once: they need to precisely inform, and they need to stimulate further curiosity. Quantum by Manjit Kumar walks this tightrope about as well as I’ve seen. Manjit Kumar exhibits both the panache of a historical dramatist and the acuity of a theoretical physicist as he brilliantly and provocatively recounts the birth of quantum theory. This book shows that the journey from Newtonian simplicity to quantum chaos was both academic and personal, it was turbulent, and it was far more human than you might expect. We meet Einstein as more than just a set of theories with a funny mustache and a crazy haircut, but as a scorned skeptic, a man who refused to accept a universe ruled by chance. We follow Max Planck and Neils Bohr and Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrodinger, and a veritable litany of others as they map out a world that refuses to play by deterministic rules. Quantum specifically asks two gnawing questions: “What is reality?” and “Can reality ever be truly known?”—two philosophical questions for the ages.

Honorable Mention:

As a sort of honorable mention, I feel like I need to also acknowledge When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut. It is technically fiction, but it’s built on the scaffolding of real events. Labatut dives deeply into the lives of some of the same figures Quantum explores … namely Einstein, Schrödinger, and Heisenberg … but instead of explaining their theories, he immerses us in the psychological and existential ramifications of their discoveries. It reads like a riveting fever dream. It’s unsettling and unforgettable. I highly recommend it.

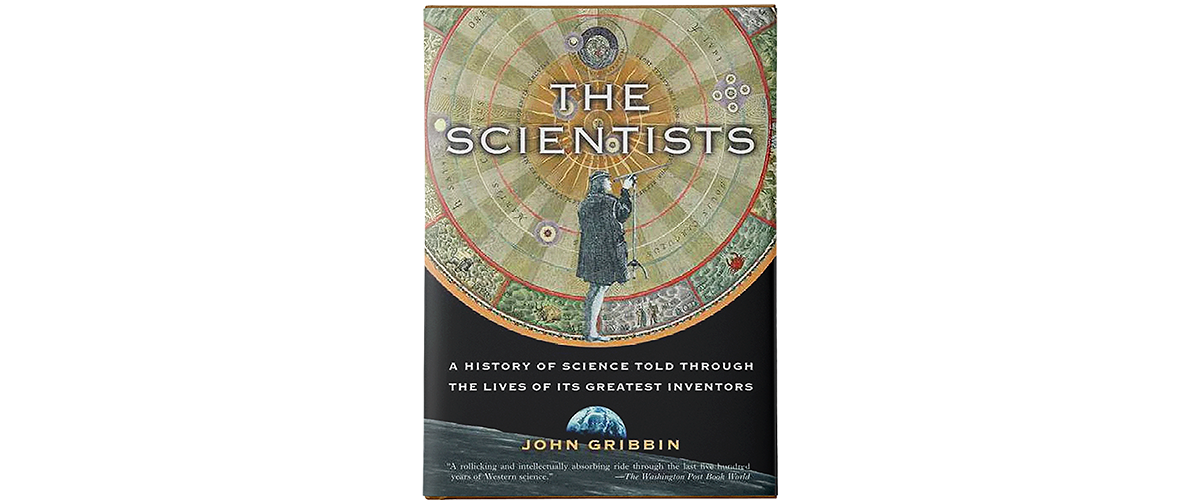

4. The Scientists by John Gribbin

I first came across The Scientists by John Gribbin while I was taking a History of Science course during the sophomore year of my undergrad studies. I’d initially picked up the book just to pull a few quotes for a paper on the significance of the Scientific Revolution—but those excerpts were so engaging, so clearly and intelligently written, that I ended up leisure-reading the whole thing. Gribbin manages to turn what could have been a dry chronology into a captivating narrative of discovery as he traces centuries of scientific breakthroughs from Copernicus to Crick and Watson. It is ambitious and accessible, and just endlessly quotable—I found myself returning to it again and again in my studies for information and inspiration. It’s a kind of single-volume biography of science itself, and it’s wonderful.

Honorable Mention:

I feel I should also give an honorable mention here to Uncentering the Earth by William T. Vollmann. This was my second foray into Vollmann’s work—my first being The Atlas, which I picked up thanks to the always spot-on recommendations of Chris from Leaf by Leaf. In this book, Vollmann breathes new life into the familiar milestones of astronomical history. His writing is vibrant and curious and unflinchingly intelligent as he transforms the story of how we came to understand our place in the cosmos into something positively electric. If you’re even slightly interested in the history of astronomy, this one is an absolute joy.

3. Physics of the Impossible by Michio Kaku

Michio Kaku’s Physics of the Impossible reads like a love letter to science fiction. I’ve been obsessed with Star Trek ever since I was a kid—largely thanks to my dad’s status as a lifelong Trekkie—and this book hits right at the heart of that obsession. Kaku takes classic sci-fi concepts like force fields and time travel and teleportation, and he explores whether they’re actually possible under the known laws of physics. His breakdown of the teleporter, in particular, is truly fascinating … and also mildly upsetting. But, y’know, even when he’s dashing childhood dreams, Kaku’s writing remains clear and approachable and terrifically paced. It’s without a doubt the most fun and accessible introduction to speculative physics I’ve ever read.

Honorable Mention:

Black Holes & Time Warps by Kip Thorne. While we’re on the subject of the physics of the impossible, I have to mention this one Black Holes & Time Warps by Kip Thorne—the physicist who helped make the black hole in Interstellar as scientifically accurate as possible. This book melds deep theoretical physics with a genuine narrative flair, and Dr. Thorne makes concepts like wormholes and time travel feel both mind-bending and deceptively understandable. It’s certainly dense, but it’s also rewarding.

2. The Fabric of the Cosmos by Brian Greene

The Fabric of the Cosmos by Brian Greene is the book that made me realize my grasp of spacetime was … tenuous at best. Dr. Greene writes with such audacious clarity that you actually begin to understand just how much you didn’t understand. He takes you deep into relativity and quantum mechanics and string theory, and even the multiverse … and he does so in a way that is astonishingly easy to follow. Concepts like quantum entanglement and spacetime foam … things that would otherwise feel impossibly abstract … they become surprisingly graspable under Greene’s guidance. It’s brain-bending in the best possible way.

Honorable Mention:

I do want to also give an honorable mention to The Particle at the End of the Universe by Sean Carroll. I’m a huge fan of Dr. Carroll—I’m not a big podcast guy, but his Mindscape podcast is one I always try to make time for—but I will admit his writing leans just a touch more dense than Brian Greene’s, and is therefore slightly less accessible. Still, The Particle at the End of the Universe is an incredible account of the search for the Higgs boson, and it is told with the insight and intellectual generosity of someone who is both brilliant and passionate about helping others understand. He brings you behind the scenes of one of the most important discoveries in modern physics—and while it certainly makes you work a little harder, the payoff is absolutely worth it.

1. “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!” by Richard P. Feynman

Topping my list is Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! by the one and only Richard Feynman. If ever there was an educator who could take esoteric concepts and make them accessible, it’s Dick Feynman. This book is essentially a collection of anecdotes and misadventures, and digressions that, taken together, feel like a manifesto that insists that intellectual curiosity is its own reward. Feynman tackles complex ideas with the enthusiasm of a child trying to figure out how a magic trick works, and somehow, it all just clicks. This book is funny and sharp, and it’s deeply inspiring. Very few books celebrate curiosity with such charm.

Honorable Mention:

As a final honorable mention, I have to shout out Alex’s Adventures in Numberland by Alex Bellos. This is the book that made me appreciate and at least partially even enjoy mathematics. In this book, Alex Bellos dives into the history and philosophy of numbers with a genuinely contagious sense of wonder. He explores mathematical concepts in a way that’s engaging and accessible, and unexpectedly delightful. To my utter surprise, I even found inspiration in these pages for a novel that I’ve been feverishly working on ever since I read this one back in December of this past year. If you’ve ever thought math just wasn’t for you, this book might just change your mind.

Closing Thoughts

At their best, nonfiction books reframe the way we see the world. Every book I’ve talked about here gave me something beyond just facts or history or theory. They gave me stories. Stories of discovery, of doubt, of stubborn curiosity and the people bold enough to ask the big questions. They reminded me that science is less about answers and more about confronting the unknown. And whether it’s quantum physics or mathematical oddities or the personal lives of brilliant minds, each of these books left a lasting impression on me. If even one of them sounds interesting to you, it is my sincere hope that you’ll check it out—because if there’s one thing I’ve learned from reading these books, it’s that reality, when told well, can be every bit as mind-blowing as fiction.

Work with me

Whether you’re looking for a subtle logo refresh or a fully custom visual design system, I’d love to hear from you.

Feel free to send an introductory email with a few details about your business. From there, we can schedule a call—or if you’re nearby, I’m happy to meet up!

Studio M

10684 Grayson CourtJacksonville, FL 32220